1. Traditional Okinawa Karate (空手)

Thus, karate is indigenous to Okinawa and had centuries of evolution before it was introduced to Japan in the early 19th century. At the time of development, Okinawa was a separate nation with close ties to China. Okinawa was later conquered by Japanese samurai in the 17th century, but karate was kept secret from the Japanese.

2. Kyudo (弓道) (Japanese Archery)

Thus, karate is indigenous to Okinawa and had centuries of evolution before it was introduced to Japan in the early 19th century. At the time of development, Okinawa was a separate nation with close ties to China. Okinawa was later conquered by Japanese samurai in the 17th century, but karate was kept secret from the Japanese.

Okinawa remained a separate nation until 1879, but the art of Karate was not introduced to the Japanese mainland until 1922 by Gichin Funakoshi. Karate, often referred to as Japanese karate or sport karate, looks similar to Okinawa karate, but Japanese karate was developed as a sport and lacked many of the pragmatic aspects of Okinawa karate. The original Okinawa karate, such as Shorin-Ryu to this day, remains mostly sport-free.

Karate developed in three villages: Shuri, Naha & Tomari. Each was a center for a different sect of society: kings and nobles, merchants, farmers and fishermen, respectively. For this reason, different styles of Te developed in each village and became known as Shuri-te, Naha-te and Tomari-te. Collectively these were called Okinawa-Te, Tode (Chinese hand) or Kara-te. The Chinese character used to write Tode could be pronounced 'kara' thus the name Te was replaced with kara te or 'Chinese hand art'. This was later changed to karate-do to adopt an alternate meaning for the Chinese character for kara, meaning 'empty'. Thus, the karate came to mean 'empty hand'. The 'do' in karate-do implies 'way' or 'path' emphasizing moral and spiritual philosophy.

Shuri te became known as Shorin-Ryu, and today, there area many branches of Shorin-Ryu as are Okinawan Ryuha and Kobudo. Shobayashi Shorin-Ryu ('small forest style'), Koybayashi Shorin-Ryu ('young forest style'), Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu ('pine forest style'), Matsumura Seito Shorin-Ryu ('orthodox' style), Sukunaihayashi (Seibukan), Ryukyu Hon Kenpo (Okinawan Kempo), Kodokai Shorin-ryu, Seidokan, Kobayashi Shorin-Ryu (Shidokan, Shorinkan, Kyudokan), Chubu Shorin-Ryu, Ryukyu Shorin-Ryu and Seiyo Shorin-Ryu. So, to say Shorin-Ryu Karate, is to almost the same as saying traditional Okinawan karate, as there are several varieties. And there is no such thing as a superior style of karate - there are only individual superior teachers and students.

As a martial art, karate has all of the traditions that help make it an art. But it can be a very powerful art for both self-defense and self-improvement. Karate not only has great punches, kicks and blocks, but its bunkai (applications from kata, or forms) incorporate weapons (kobudo) and jujutsu (throws and chokes). Another powerful art - Naha te became known as Goju-Ryu. The Okinawan Goju remained an art, unlike the Japanese Goju-Ryu that became a sport. There are many aspects of 'traditional karate' that are filled with philosophy and traditions and this is the primary reason that traditional karate is recognized as the #1 Martial Art in the world. In addition to self-defense, karate provides people with self-improvement, positive health, and longevity.

2. Kyudo (弓道) (Japanese Archery)

|

| Ya (arrows) |

Few martial arts can compete with the traditional art of kyudo - Japanese archery. This is because it is a very traditional martial art with no competition. Traditions are necessary and you can not learn this art without traditions, traditions and more traditions.

Japanese archery – is typically practiced in a dojo (道場) built for archery. Practitioners of this art take it seriously - and it has been part of the Japanese culture for hundreds of years. It is associated with the feudal samurai education, giving this art a distinct lineage. The art is known as Kyūdō (弓道). Kyudo translates as the way of the bow and the bow used in this art is awkward to archers from the West. But if Westerners were required to learn kyudo, we would likely see a change in our society for the better - because kyudo requires patience and respect - two things notably absent in modern society. Kyudo is a beautiful martial art, but finding a teacher in the West is difficult.

|

| Yumi sho for close quarters |

Instead of being neatly divided into two, the hand grip splits the bow into thirds – one third below the grip and two-thirds above. The bow's shape is unique and has been unchanged for two thousand years. It is the only bow whose handling point is not set in the center, this difference has created uniqueness in Japanese archery.

Like all martial arts, the history and evolution of Kyudo leads to many paths and myths. The Japanese bow was created centuries ago. In the Chinese chronicle Weishu (written before 297 AD) it described the Japanese bow, thus it existed nearly three centuries after the birth of Christ and who knows how much earlier.

There are various styles of kyudo, just as there are in karate (空手) and jujutsu (柔術). Some suggest the first style of kyudo (or kyujutsu) was Henmi-ryū founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. Others disagree and suggest the first ryuha was formed earlier – such as Taishi-Ryu, believed to have been founded by Shotoku Taishi (574-622 AD).

Some other styles of kyudo include Takeda-Ryu and Ogasawara-Ryu that were founded by descendants of Henmi Kiyomitsu. These styles were created to satisfy a need for archers during the five-year war of 1180–1185 AD, when Ogasawara Nagakiyo taught yabusame (mounted archery) to supplement unmounted archers. Yabusame-Ryu became very prominent and is still practiced today. In the modern form, archers ride at a full gallop and shoot at three targets set up in intervals. The archer is considered skillful when all three targets are hit by an arrow.

|

| "Japanese Garden"- colored pencil sketch by Hausel, Soke |

In the latter part of the 15th century Heki Danjō Masatsugu (1443-1502) revolutionized Japanese unmounted archery with a new approach known as hi-kan-chū (fly, pierce, center) that in now standardized for Japanese archery.

The use of a bow as an effective weapon of war ended after Europeans arrived in Japan in 1542 AD carrying muskets. Even armed with muskets, the bow was carried alongside warriors with muskets for years because of its longer reach, accuracy, and faster reloads. But the musket provided a different advantage - it did not require much training - just load, point and shoot. Thus in 1575 AD, an army of peasants armed with muskets annihilated traditional samurai archery cavalry in battle – this sealed the fate of archery in war.

During changes by Japan to open its borders to the outside world beginning in the Meiji era (1868–1912), samurai lost status. All martial arts including kyudo, saw a significant decrease in appreciation. So, to preserve Japanese archery, a group of kyudo masters gathered in 1896 with the thought of preserving traditional archery. Honda Toshizane, a kyudo Sensei at Imperial University of Tokyo, created a hybrid style called Honda-Ryu. It wasn’t until 1949 before the All Japanese Kyudo Federation (Zen Nihon Kyudo Renmei) published guidelines for competition and graduation. Today, many Kyudo schools emphasize aesthetics and training, while a few emphasize efficiency. Some teach archery as meditation while others focus on competition. It is the goal of many kyudo dojo to follow shin-zen-bi, roughly "truth-goodness-beauty".

Kyudo like all forms of budō includes moral and spiritual development. There are many schools that focus on kyudo as sport with marksmanship being paramount. To give oneself completely to shooting is a spiritual goal achieved by perfection of both the spirit and shooting technique. Many kyudo practitioners believe that competition, examination, and opportunities that place the archer in uncompromising situations are important. However, other schools feel competition erodes moral and spiritual values, and avoid all competitions to focus on technique and building the individual character.

The kyudo dojo varies in style and design. Most have an entrance with a large training area. The training area typically has a wooden floor with high ceiling, practice targets, and a large open wall with sliding doors, such that when these are open, the dojo overlooks a grassy area and a separate building known as matoba which houses a dirt hillock and targets that are placed 89.6 feet from the dojo floor.

Starting out in kyudo, the student first trains with a rubber practice bow. The purpose of this is to get the student to focus on movement and technique. Advanced beginners and advanced shooters practice shooting at makiwara, a specially designed straw target that should not to be confused with makiwara used in karate. Archers shoot at the makiwara at a very close distance (about seven feet) so that the archer can focus on refining techniques.

|

| Yumi (Japanese bow). |

Using a system which is common to modern martial arts, some (but not all) kyudo schools hold examinations. If the archer passes, he/she can be graded to kyū or dan. However, most traditional (non-competitive) schools use the old menkyo (license) system of koryū budō.

In Japan, kyu ranks in kyudo are only tested in high schools and colleges, with adults skipping these to move straight to first dan. While kyudo’s kyu and dan levels are similar to those of other budō systems, colored belts or similar external symbols of one's level are not worn by kyudo practitioners. While kyudo is primarily viewed as an avenue toward self-improvement, there are kyudo competitions or tournaments whereby archers practice in a competitive style.

Competition is held with a great ceremony. The archer must also perform an elaborate entering procedure where the archer will join up to four other archers who enter the dojo, bow to the adjudicators, step up to the back line and then kneel in a form of seiza. The archers bow to the targets in unison, stand, and take three steps forward to a firing line and kneel again. Each archer stands and fires one after another at the respective targets, kneeling in-between each shot, until they have exhausted their supply of arrows (generally four).

3. Kenjutsu (剣術), Iaidō (居合道); Battōjutsu (抜刀術)

The arts of the samurai sword (katana). According to wiki, kenjustu is the umbrella term covering all types of ancient koryu schools of Japanese swordsmanship established and practiced prior to the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Although, some modern equivalents are included. Kenjutsu is typically practiced as a combat art using bokken (wooden swords) or jo (4-foot staff). Sparring is restricted to kendo and kenjutsu; whereas, arts such as iaido, are similar, but focus on kata rather than randori.

The arts of the samurai sword (katana). According to wiki, kenjustu is the umbrella term covering all types of ancient koryu schools of Japanese swordsmanship established and practiced prior to the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Although, some modern equivalents are included. Kenjutsu is typically practiced as a combat art using bokken (wooden swords) or jo (4-foot staff). Sparring is restricted to kendo and kenjutsu; whereas, arts such as iaido, are similar, but focus on kata rather than randori.

In iaidō, the student begins training with bokken (wooden practice sword) and later switches to an iaitō (dull-edged practice sword). Shinken (live blades) are almost never used because of the extreme danger. Because iaidō is practiced with a weapon, nearly all training is by kata that includes drawing the weapon followed by cuts and finishing with ceremonial blade de-blooding and replacing the weapon back into the scabbard (saya).

Wikipedia reports styles of iaidō include: Muso Jikiden Eishin-Ryu, Muso Shinden Ryu, Mugai-Ryu, Jikyo-Ryu, Suio-Ryu, Motobu Udundi (Okinawan), Shindō Munen-ryu, Shinkage-ryū, Hōki-ryū, Tatsumi-ryū, Tamiya-ryū, Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū, Takenouchi-ryū, Eishin-ryū, and Shinjo-ryū.

Sword testing, known as tameshigiri was designed to test the blade’s sharpness and the practitioner’s abilities to cut materials. Today, we often see cuts of matting or straw on a vertical pole. In the past, it was not uncommon for Japanese to test on cadavers of executed criminals. Iaido is one of many samurai or pechin arts. Some of the many other samurai arts include traditional jujutsu, tessenjutsu, hojojutsu, hanbojutsu, naginatajutsu, kenjutsu, kendo and sojutsu. Such old koryu arts all employ considerable tradition and ceremony.

3. Kenjutsu (剣術), Iaidō (居合道); Battōjutsu (抜刀術)

The arts of the samurai sword (katana). According to wiki, kenjustu is the umbrella term covering all types of ancient koryu schools of Japanese swordsmanship established and practiced prior to the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Although, some modern equivalents are included. Kenjutsu is typically practiced as a combat art using bokken (wooden swords) or jo (4-foot staff). Sparring is restricted to kendo and kenjutsu; whereas, arts such as iaido, are similar, but focus on kata rather than randori.

The arts of the samurai sword (katana). According to wiki, kenjustu is the umbrella term covering all types of ancient koryu schools of Japanese swordsmanship established and practiced prior to the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Although, some modern equivalents are included. Kenjutsu is typically practiced as a combat art using bokken (wooden swords) or jo (4-foot staff). Sparring is restricted to kendo and kenjutsu; whereas, arts such as iaido, are similar, but focus on kata rather than randori.

Iaijutsu, iaidō and battōjutsu are fast draw Japanese sword (katana) arts designed to develop fast draw with follow-up attacks using a Japanese sword. These are similar and generally only differ in training methods. For instance, battōjutsu incorporates multiple cuts following the sword draw; while iaidō emphasizes reaction to unknown scenarios, or a reaction to sudden and swift attacks.

|

| Iaido - Japanese sword |

Wikipedia reports styles of iaidō include: Muso Jikiden Eishin-Ryu, Muso Shinden Ryu, Mugai-Ryu, Jikyo-Ryu, Suio-Ryu, Motobu Udundi (Okinawan), Shindō Munen-ryu, Shinkage-ryū, Hōki-ryū, Tatsumi-ryū, Tamiya-ryū, Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū, Takenouchi-ryū, Eishin-ryū, and Shinjo-ryū.

Sword testing, known as tameshigiri was designed to test the blade’s sharpness and the practitioner’s abilities to cut materials. Today, we often see cuts of matting or straw on a vertical pole. In the past, it was not uncommon for Japanese to test on cadavers of executed criminals. Iaido is one of many samurai or pechin arts. Some of the many other samurai arts include traditional jujutsu, tessenjutsu, hojojutsu, hanbojutsu, naginatajutsu, kenjutsu, kendo and sojutsu. Such old koryu arts all employ considerable tradition and ceremony.

|

| Training in kenjutsu - the art of the sword. |

4. Toide

Toide, originally known on Okinawa as Goten-Te (palace hand), is also known as Motobu-Ryu Toide and Motobu Udun Di (Motobu's royal-place hand), was mainly taught to Okinawan martial artists. The original system includes traditional dance, throws and weapons. The Juko-Ryu Aiki Inyo Toide of Juko Kai International, is one of the more powerful martial arts in the world and exhibits similarities to Motobu-Ryu Toide and Seidokan Toide of Okinawa, but does not include O-dori (dance) and also incorporates Shitai Kori along with weapons such as katana (sword), yari (spear), naginata (pole arm) and bo (staff).

5. Jujutsu (柔術)

10. Hanbojutsu (半棒)

Toide, originally known on Okinawa as Goten-Te (palace hand), is also known as Motobu-Ryu Toide and Motobu Udun Di (Motobu's royal-place hand), was mainly taught to Okinawan martial artists. The original system includes traditional dance, throws and weapons. The Juko-Ryu Aiki Inyo Toide of Juko Kai International, is one of the more powerful martial arts in the world and exhibits similarities to Motobu-Ryu Toide and Seidokan Toide of Okinawa, but does not include O-dori (dance) and also incorporates Shitai Kori along with weapons such as katana (sword), yari (spear), naginata (pole arm) and bo (staff).

5. Jujutsu (柔術)

|

| Pressure point attacks employed in jujutsu are also found in many other martial arts including karate, judo, aikido, etc. |

Jujutsu is a combat art developed by samurai centuries ago. The martial art had an evolution separate from karate. Karate, which focuses on kicks and punches is indigenous to Okinawa and became combat form and later an art for peasants and Okinawan royalty. Jujutsu, indigenous to Japan, had a different purpose designed for hand to hand combat to defend against a heavily armed samurai clad in armor. Punching an enemy wearing armor with bare hands and feet does not seem like a bright idea, thus the samurai developed throwing techniques (nage waza), foot sweeps (ashi barai) and trips to defend against other armored and armed samurai.

Along with throws, the jujutsuka learned unique strikes (atemi) to disturb the balance of the samurai (whether armored or unarmored). These atemi were designed to unbalance an opponent and generate a shock wave propagated through armor.

Today we recognized two general categories of jujutsu: (1) Koryu (ancient)traditional jujutsu which was designed to defend against armed samurai with or without armor, and (2) modern Gendai jujutsu that favors self-defense applications used in sport and modern combat martial arts. Many Gendai schools lack lineage and traditions (i.e., Brazilian jujutsu). Then there are arts, such as Juko Ryu jujutsu, that would have been at home on any Japanese battlefield.

In both old style and modern jujutsu, atemi is important. Before one can effectively throw an attacker, the aggressor’s balance should be disturbed. In Arizona we find (thanks to a questionable grant - after all we did not need some government research project to tell us what we already know in Mesa and Gilbert in the East Valley of Phoenix) people sweat more than in any other state. To grab and throw someone in Arizona is much more difficult than in Wyoming (where it is dry and cold), simply because sweaty people are slippery and difficult to grasp. But then again, in Wyoming, throwing someone while standing on ice or snow may not be the best idea.

|

| Training in hojojutsu - prisoner restraints. Casper dojo, Wyoming. |

According to the Overlook Martial Arts Dictionary, atemi translates as "body strikes". It refers to "…a method of attacking the opponents pressure points". In A Dictionary of the Martial Arts there is a more detailed description. It states that an atemi is... "…aimed at the vital or weak points of an opponent's body in order to paralyze by means of intense pain. Such blows can produce loss of consciousness, severe trauma and even death…the smaller the striking surface used in atemi, the greater the power of penetration and thus the greater the effectiveness of the blow". This may be true in modern jujutsu, but in the ancient styles of jujutsu, pressure points for armored samurai were not important on a battlefield. A samurai covered with armor, had few if any exposed pressure points.

Today, atemi is used to provide a distraction leading to a throw, joint lock, or choke. This is done by redirecting an opponent into a throw through attacking vital points to cause pain or loss of consciousness. In other words, it is easier to throw an unconscious or disoriented aggressor and one who is already moving in the direction of the throw. One common atemi is a palm strike along the jaw line, ear (mimi) or neck (kubi). This also was likely used against armored samurai. Even with a helmet, a powerful open hand "teisho uchi" strike to the side of a helmet would ring one’s bell.

|

| Classical restraint used in jujutsu employing arm bar and wrist lock. Arizona Hombu photo. |

The term ‘jūjutsu’ was coined in the 17th century, after it became a blanket term for a wide variety of grappling combat forms. Jujutsu (柔術) translates as the „art of softness‟or „way of yielding‟. The oldest forms of jujutsu are referred to as Sengoku jujutsu or Nihon Koryu Jujutsu. These were developed during the Muromachi period (1333–1573 AD) and focused on techniques that assisted samurai in defeating unarmed, lightly armed, and heavily armed and armored samurai – thus a greater emphasis was placed on joint locks and throws.

Later in history, other koryu developed that are similar to many modern styles. Many of these are classified as Edo jūutsu and were founded in the Edo Period (1625-1868 AD) of Japan. Most are designed to deal with opponents without armor. Edo jujutsu commonly emphasizes use of atemi waza. Inconspicuous weapons such as a tantō( knife) and tessen (iron fans) are included in Edo jūjutsu curriculum.

Another interesting art taught in Sengoku and Edo jujutsu systems is known as hojojutsu. This involves a cord used to restrain or strangle an attacker. Such techniques have faded from most modern jujutsu styles, although Tokyo police units still train in hojojutsu and carry a hojo in addition to handcuffs.

|

Special training in jujutsu - use of expandable baton. University of Wyoming photo

|

Weapons training were extremely important to Samurai. Koryu schools included the bo (six-foot staff), hanbo (three-foot staff), jo (4-foot staff), tachi (sword), wakizashi (short sword), tanto(knife), jitte (short one hook truncheon), yari (spear), naginata (halberd), ryofundo kusari (weighted chain) and bankokuchoki (knuckle-duster).

Edo jujutsu was followed by development of Gendai Jujutsu at the end of the Edo Period. Gendai, or modern Japanese jujutsu, shows influence of traditional jujutsu. Goshin Jujutsu styles developed at about the same time, but the Goshin styles are only partially influenced by traditional jujutsu and have mostly been developed outside of Japan.

Today, many Gendai jujutsu styles have been embraced by law enforcement officials and continue to provide foundations for specialized systems by police officials. The best known of these is Keisatsujutsu (police art) or Taihojutsu (arresting art) formulated by the Tokyo Police.

|

| Soke Hausel teaches taiotoshi (body leg drop) at an outdoor clinic in Utah |

Jujutsu is the basis for many military unarmed combat training programs for many years and there are many forms of sport (non-traditional) jujutsu, the most popular being judo, now an Olympic sport. Some examples of martial arts that have been influenced by jujutsu include Aikido, Hapkido, Judo, Sambo, Kajukenbo, Kudo, Kapap, Kempo and Ninjutsu as well as some styles of Japanese Karate, such as Wado-ryu Karate, which is considered a branch of ShindōYōhin-ryūJujutsu.

The training uniform (keikogi) provides an excellent indicator of traditions in a jujutsu dojo. Traditional schools wear plain white gi often with a dark hakama (the most colorful uniform might be plain black or the traditional blue of quilted keikogi. Lack of ostentatious display, with an attempt to achieve or express the sense of rustic simplicity is common in traditional arts. The use of the traditional (Shoden, Chuden, Okuden, Kirigami and Menkyo Kaiden) ranking system is also a good indicator of traditional jujutsu. These are parallel to the common dan-i (kyu/dan) ranking used in traditional karate.

6. Okinawan Kobudo (沖縄古武道)

Okinawan kobudo - the art of the peasant tool weapons. Today, the kobudo arts are blended with many of the Okinawan karate arts, in particular with Shorin-Ryu Karate. Kobudo may have developed following a proclamation by Okinawan King Shoshin in 1480 AD that banned bladed weapons on the island nation. So, some Okinawans learned to use tools of trade for weapons. Farmers experimented with bo (6-foot staff) used to transport goods, fishermen used rope and rocks to produce suruchin and merchants used rice grinder handles & horse bridles to develop tonfa while stirrups & horseshoes became tekko.

Traditional Okinawan weapons are numerous and include tuja (3-prong spear), nunchaku, sansetsukun (aka sanbon nunchaku) or 3-sectional staff, tonfa (side-handle baton), sai (fork-like weapon), manji no sai (sai with one prong directed in opposite direction), nuntei-bo (bo with manji no sai attached to one end), kama (sickle), kusarigama (kama with attached chain and weight), nitanbo (two sticks), bo or rokushaku bo (staff), hasshaku bo (8-shaku staff), kyushaku bo (9 shaku staff), jo (4 shaku staff), sanjaku bo or hanbo (3-shaku staff), kubotan (short stick), eku (oar), ra-ke (rake), kuwa (hoe), hari (fish hooks), nireki (hand rakes), surichin (weighted rope or chain), tinbe (short spear or machete with leather shield), tetsubo, suruji, tekko (horse stirrups), gekiguan (stick with weighted chain or rope attached to one end), techu (short stick or metal rod with center ring), take no bo (cane), uchi bo (two rods of unequal length attached by rope or chain), kasa(umbrella), ogi (fan), kanzashi (hairpin), kisiru (tobacco pipe), mame (dried beans or pebbles for throwing), kaki (firearms) & more. At the Arizona Hombu, members learn traditional weapons including some everyday tools in our homes, cars and office.

7. Gung Fu (功夫)

Gung Fu, also known as Kung Fu and Wushu. Legend states a Buddhist monk named Bodhidharma traveled from India to northern Henan province of China where he taught Zen at the Shaolin Temple around 525 AD. When Bodhidharma arrived at Shaolin-si (small forest temple), he began lectures but found most monks unfit & lazy. Bodhidharma realized the solution was to improve physical conditioning of the monks in order to improve their minds; thus, he began teaching physical exercises with meditation known as 'Shi Po Lohan Sho' (18 hands of Lohan) reputed to be a fighting system. The blending of Lohan with Zen evolved into the first martial art. To be a martial 'art' there must be intrinsic value for the spirit, body and soul.

8. Sojutsu (槍) - Naginatajutsu (薙刀)

Sojutsu is the art of the spear while naginata is the art of the pole arm. Both of these Japanese arts are very traditional and it is rare to find anyone in North America that teaches these. Sojutsu is taught at few schools in North America, but offered in some schools in Japan. Naginata is much the same, but there are naginata associations.

9. Ninjutsu (忍術)

Ninjutsu (忍術), sometimes used interchangeably with the modern term ninpō (忍法)

6. Okinawan Kobudo (沖縄古武道)

Okinawan kobudo - the art of the peasant tool weapons. Today, the kobudo arts are blended with many of the Okinawan karate arts, in particular with Shorin-Ryu Karate. Kobudo may have developed following a proclamation by Okinawan King Shoshin in 1480 AD that banned bladed weapons on the island nation. So, some Okinawans learned to use tools of trade for weapons. Farmers experimented with bo (6-foot staff) used to transport goods, fishermen used rope and rocks to produce suruchin and merchants used rice grinder handles & horse bridles to develop tonfa while stirrups & horseshoes became tekko.

Traditional Okinawan weapons are numerous and include tuja (3-prong spear), nunchaku, sansetsukun (aka sanbon nunchaku) or 3-sectional staff, tonfa (side-handle baton), sai (fork-like weapon), manji no sai (sai with one prong directed in opposite direction), nuntei-bo (bo with manji no sai attached to one end), kama (sickle), kusarigama (kama with attached chain and weight), nitanbo (two sticks), bo or rokushaku bo (staff), hasshaku bo (8-shaku staff), kyushaku bo (9 shaku staff), jo (4 shaku staff), sanjaku bo or hanbo (3-shaku staff), kubotan (short stick), eku (oar), ra-ke (rake), kuwa (hoe), hari (fish hooks), nireki (hand rakes), surichin (weighted rope or chain), tinbe (short spear or machete with leather shield), tetsubo, suruji, tekko (horse stirrups), gekiguan (stick with weighted chain or rope attached to one end), techu (short stick or metal rod with center ring), take no bo (cane), uchi bo (two rods of unequal length attached by rope or chain), kasa(umbrella), ogi (fan), kanzashi (hairpin), kisiru (tobacco pipe), mame (dried beans or pebbles for throwing), kaki (firearms) & more. At the Arizona Hombu, members learn traditional weapons including some everyday tools in our homes, cars and office.

7. Gung Fu (功夫)

Gung Fu, also known as Kung Fu and Wushu. Legend states a Buddhist monk named Bodhidharma traveled from India to northern Henan province of China where he taught Zen at the Shaolin Temple around 525 AD. When Bodhidharma arrived at Shaolin-si (small forest temple), he began lectures but found most monks unfit & lazy. Bodhidharma realized the solution was to improve physical conditioning of the monks in order to improve their minds; thus, he began teaching physical exercises with meditation known as 'Shi Po Lohan Sho' (18 hands of Lohan) reputed to be a fighting system. The blending of Lohan with Zen evolved into the first martial art. To be a martial 'art' there must be intrinsic value for the spirit, body and soul.

|

| Sojutsu - training with yari (spear) |

Sojutsu is the art of the spear while naginata is the art of the pole arm. Both of these Japanese arts are very traditional and it is rare to find anyone in North America that teaches these. Sojutsu is taught at few schools in North America, but offered in some schools in Japan. Naginata is much the same, but there are naginata associations.

Ninjutsu (忍術), sometimes used interchangeably with the modern term ninpō (忍法)

10. Hanbojutsu (半棒)

The hanbo, or ‘half-bo’ is a practical martial arts weapon. Similar to hanbo is the 'bo'. The bo is a 6-foot staff (or stick) used for transporting goods over one's shoulders in many regions of Asia; thus the hanbo represents a stick half the length of a bo. Hanbo-jutsu is incorporated in other traditional martial arts such as some forms of traditional jujutsu and some forms of traditional ninjutsu. It is also part of the Seiyo Shorin-Ryu Karate system.

SUMMARY

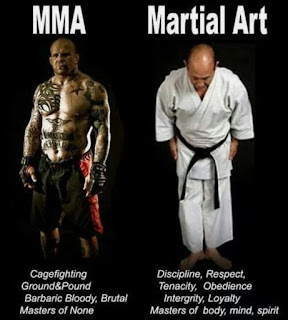

Some may wonder why MMA is not mentioned. Simply, MMA is not a traditional martial art and does not even meet a simple definition for martial art. To be martial art, a fighting system must employ character development, philosophy, and similar traditions for self-improvement of the mind, body and spirit. When the first martial art was developed possibly 1500 years ago, Boddhidarma, a Buddhist monk from India, combined a fighting system known as shi po Lohan sho with Zen, which became known as martial art and was developed over the centuries at the Shaolin Temple. MMA employs no redeeming values for personality.

One art that was considered by our committee, was not included in the top ten, only because it is used in many martial arts - but some systems like Juko Kai, Seiyo Kai, Shaolin Gung Fu and Kyokushi Kai have taken to new levels. Known in Japanese as Kote Kitae, a body hardening martial art can be blended with other martial arts. But few styles have taken it to the level of Juko Kai and Shaolin Gung Fu.

SUMMARY

Some may wonder why MMA is not mentioned. Simply, MMA is not a traditional martial art and does not even meet a simple definition for martial art. To be martial art, a fighting system must employ character development, philosophy, and similar traditions for self-improvement of the mind, body and spirit. When the first martial art was developed possibly 1500 years ago, Boddhidarma, a Buddhist monk from India, combined a fighting system known as shi po Lohan sho with Zen, which became known as martial art and was developed over the centuries at the Shaolin Temple. MMA employs no redeeming values for personality.

One art that was considered by our committee, was not included in the top ten, only because it is used in many martial arts - but some systems like Juko Kai, Seiyo Kai, Shaolin Gung Fu and Kyokushi Kai have taken to new levels. Known in Japanese as Kote Kitae, a body hardening martial art can be blended with other martial arts. But few styles have taken it to the level of Juko Kai and Shaolin Gung Fu.